When fitting hearing aids, audiologists in New Zealand follow strict best practice guidelines set by MNZAS. These guidelines ensure that every fitting begins with a thorough needs assessment. But while the guidelines provide the scientific foundation, the process of programming hearing aids is far more layered and nuanced than many people realise.

Needs Assessment: More Than Just Choosing a Style

The first step is understanding what a person is missing in their life because of hearing loss. This isn’t simply about choosing a device that looks discreet — it’s about uncovering lifestyle needs, safety concerns, and personal preferences.

- Lifestyle considerations:

Many people assume that miniature receiver‑in‑the‑canal (mRITC) aids are the default option. While common, they are not always the most suitable. For someone working outdoors, managing livestock, or supporting people with special needs, canal‑based devices such as in‑the‑canal (ITC), invisible‑in‑the‑canal (IIC), or Lyric devices may be better. These sit securely inside the ear canal, avoiding interference from hats, bush growth, or accidental knocks. - Safety considerations:

A person with chronic otitis externa (ear infections) needs to understand that canal‑based devices may complicate their condition. In such cases, alternatives like bone‑conduction hearing aids or cochlear implants may be safer and more effective. - Technology considerations:

Beyond style, the audiologist must explore speech de‑noising and speech‑enhancing technology in order to support a person’s lifestyle. Connectivity is also critical — many patients want seamless integration with smartphones, Bluetooth devices, and streaming platforms.

Once all options are explained, the audiologist guides the patient through a trial period. Comfort and feedback are non‑negotiable: if a device isn’t comfortable or squeals, it simply won’t be worn.

The Science of Programming: Data Matters

Programming hearing aids is not guesswork. It requires precise data and careful measurement.

- Accurate Audiogram

The audiogram is the foundation of programming. Yet errors can occur — for example, if ear canals are unusually shaped or if bone conduction headphones are placed incorrectly. A flawed audiogram leads to flawed programming. - Ear Canal Resonance

The ear canal naturally shapes sound before it reaches the eardrum. Measuring these resonant properties ensures the right amount of gain is applied for different sound levels. Without this, amplification may be uneven or distorted. - Natural Sound Entry

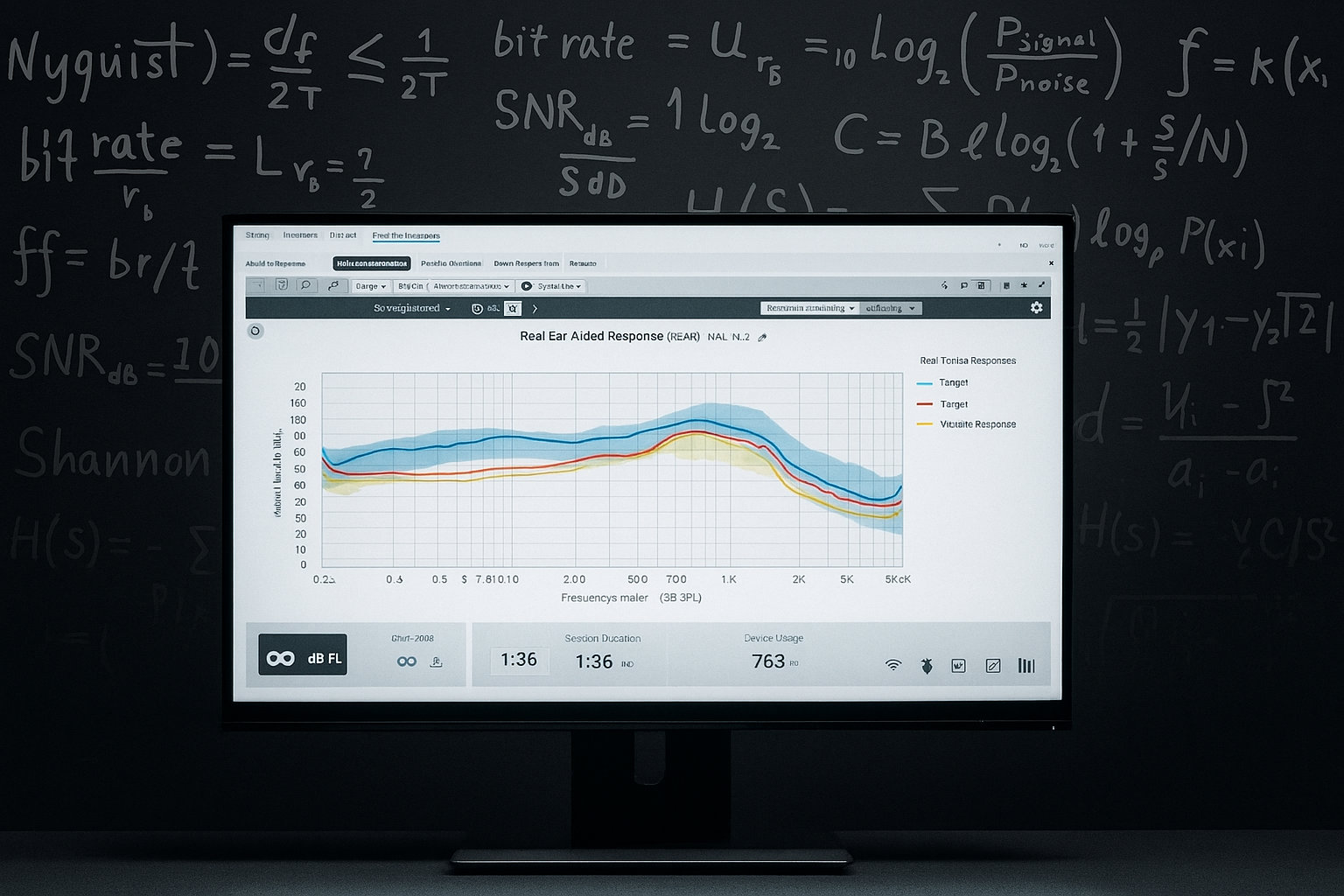

With the aid in place, we must know how much sound enters the canal naturally. Over‑amplifying low frequencies that already naturally enter through the ear canal past the hearing aid can distort a person’s own voice. Similarly, if not enough low frequencies enter the canal past the hearing aid and the programming under-amplifies in pitches, the result is the same – a person’s own voice can sound distorted – usually loud, often “boomy” – and almost always objectionable. - Programming to Formula

Only when these conditions are satisfied can programming begin. The audiologist plays speech sounds through a speaker, records what the aids deliver to the eardrum, and adjusts gain until the performance matches a mathematical formula. This formula is built on decades of linguistics, psychoacoustics, acoustics, engineering, and physiology.

A “good fit” is when the hearing aid’s output matches this formula within defined tolerances. At this point, the hearing loss is said to be corrected — at least scientifically.

Science Meets Art

Best practice guidelines ensure accuracy, but they are only the beginning. Audiologists sometimes go beyond formulas and measuring hearing aid output. And that’s because a fitting that looks perfect on-screen may fail in practice — in restaurants, at concerts, or in conversations with friends.

That’s why the art of hearing aid programming matters. One of the most meaningful ways audiologists can learn about how hearing aids behave is to wear hearing aids themselves – no hearing loss required. In fact, it is especially beneficial for audiologists with normal hearing. With normal hearing one can be quite fussy about programming, and formulas, and with ultimately with recommending any one particular hearing aid brand – and that’s because how the aid sounds is benchmarked to natural hearing. That can be never be taught. It has to be lived: at restaurants, watching TV, in meetings, appreciating how music feels through Bluetooth or live performance. Afterall, those are some of the most common listening scenarios for customers who wear hearing aids.

At hear., fittings are never rushed. Science provides the foundation, but empathy and artistry transform hearing aids from devices into life‑changing companions.

Why This Matters

- Patients deserve more than formulas. Hearing aids should enrich life, not just correct loss.

- Comfort and usability are critical. If aids aren’t comfortable or practical, they won’t be worn.

- Programming is iterative. It requires testing, listening, and adjusting until the patient feels confident.

- Science and art must work together. Guidelines ensure safety, but artistry ensures joy.

Conclusion:

The science of hearing aid programming is rigorous, precise, and essential. But it is only the beginning. True success lies in blending science with art — ensuring that hearing aids don’t just meet clinical standards, but help people reconnect with the sounds that matter most.